Harlene Rosen: The Forgotten Muse Behind a Rock and Roll Revolution

Harlene Rosen: The Muse Who Faded from the Song, But Not from the Story

The history of rock and roll is written in lyrics, chords, and legendary names. But between the lines, in the silent spaces between the notes, lie the stories of the muses—the individuals who ignited the creative fires that gave us the songs that defined generations. Few figures in this shadowy pantheon are as intriguing, or as consequential, as Harlene Rosen. To many, she is a footnote, a passing mention as “Bob Dylan’s high school girlfriend.” Yet, to understand the formation of a poetic voice that would change the world, one must understand Harlene Rosen. Her brief but intense relationship with a young Robert Zimmerman, before he became Bob Dylan, represents a foundational chapter in the artist’s life. It was a romance of youth, intellectual sparring, and ultimately, a bitter rupture that provided the kindling for some of Dylan’s earliest, most venomous, and most revealing songs. This article delves beyond the myth, seeking the person behind the name, exploring the cultural context of the muse, and examining how a relationship from the halls of Hibbing High School echoed through the annals of music history. The story of Harlene Rosen is not just a piece of trivia; it is a lens through which to view the painful, beautiful, and often exploitative alchemy of turning personal experience into enduring art.

The Crucible of Youth in Hibbing, Minnesota

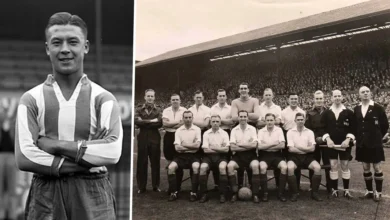

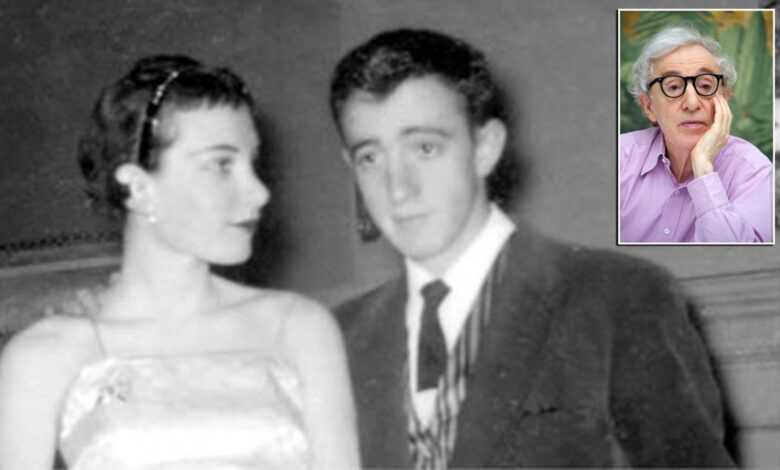

To grasp the significance of Harlene Rosen in Bob Dylan’s narrative, we must first travel to the iron-ore country of northern Minnesota. Hibbing in the 1950s was a town of stark contrasts—a prosperous mining community with a deep-seated, conservative heart. Robert Zimmerman, a restless Jewish boy with a love for rhythm and blues, piano, and poetry, felt like an alien in this environment. His aspirations stretched far beyond the Mesabi Iron Range, toward the mythical beats of Kerouac and the rebellious sounds of early rock. It was in this stifling atmosphere that he met Harlene Rosen.

She was, by many accounts, his intellectual equal and a formidable personality in her own right. Bright, articulate, and confident, Harlene Rosen was not a passive admirer but an active participant in their dynamic. Their bond was built on shared conversations about philosophy, literature, and music—a meeting of minds for a young man starving for such connection. This period was Dylan’s formative incubation, and Harlene Rosen was a central figure in that private world, offering both companionship and a challenging mirror for his burgeoning identity.

The Muse as Catalyst in Artistic Mythology

The concept of the muse is as old as art itself, often romanticized as an ethereal figure of inspiration. In the rock and roll canon, this role is frequently gendered and simplified: the woman who inspires the heartbreak anthem, the love ballad, or the song of longing. Figures like Pattie Boyd (for George Harrison and Eric Clapton) or June Carter (for Johnny Cash) are celebrated in this light. However, the reality of the muse is far more complex and often more transactional. The artist draws from the well of lived experience—joy, conflict, passion, and pain—transforming real people into symbols within their work.

Harlene Rosen occupies a specific and raw niche within this tradition. She was not the muse of the superstar Dylan, but of the teenager and the fledgling folk singer finding his voice. Her importance lies in her timing. She was present at the absolute genesis, influencing the development of Dylan’s lyrical attitude and his understanding of interpersonal dynamics as fuel for creativity. Her story forces us to confront the human cost of being immortalized in song, especially when the portrait is less than flattering. The experience of Harlene Rosen underscores that being a muse is not always about being idolized; sometimes, it is about being etched into history as the antagonist in the artist’s personal drama.

A Relationship Forged in Intellectual Fire

Accounts from classmates and Dylan’s own semi-fictionalized recollections paint a picture of a fiery, competitive relationship. This was not a simple teenage romance. Dylan, perpetually shape-shifting and building his personal mythology, found in Harlene Rosen a counterpart who could engage with him on a cerebral level. They debated, they clashed, they pushed each other. She was reportedly strong-willed and sharp-tongued, qualities that both attracted and ultimately clashed with Dylan’s own mercurial nature.

This intellectual sparring was likely a key source of her catalytic power. For an artist like Dylan, who would soon master the art of lyrical combat and pointed observation, having a real-life opponent of equal wit was priceless training. The relationship with Harlene Rosen provided a sandbox for developing the persona of the clever, slightly cynical, emotionally guarded observer that would define his early work. She was, in essence, his first great critic and his first great subject, rolled into one.

The Rupture and the Birth of “Song to Woody”

While the precise details of their breakup are shrouded in the mists of adolescent drama, it is known to have been acrimonious. Dylan, by 1959, was desperate to leave Hibbing and his past behind, heading first to the University of Minnesota and then, fatefully, to New York City. The end of his tie with Harlene Rosen was a clean severance from his hometown identity. It was a necessary rupture for the artist he needed to become, but a deeply personal one for the people involved.

Interestingly, one of Dylan’s earliest composed songs, the talking blues “Song to Woody,” written in 1961 about his hero Woody Guthrie, contains a cryptic and often-overlooked reference. In its final verse, Dylan sings of the people he’s met in New York, including “that little boxer girl from Hibbing, Minnesota.” While not explicitly named, the consensus among biographers points strongly to Harlene Rosen, referencing her reported pugilistic spirit. This fleeting mention is a ghost from his past, a quiet acknowledgment amid his forward-looking homage, showing how she lingered in his subconscious even as he was inventing his future.

The Scorn of “Ballad in Plain D”

If the reference in “Song to Woody” is a ghost, then the song “Ballad in Plain D” is a full-bodied haunting. Recorded for the 1964 album Another Side of Bob Dylan, it is one of the most brutally personal and vindictive songs in his entire catalog. An eight-minute-long, searingly detailed account of a relationship’s bitter end, it leaves little to the imagination. Dylan lashes out not only at a former lover but savagely attacks her sister, describing a domestic scene of accusation and emotional wreckage.

While Dylan never officially confirmed the subject, the biographical alignment is undeniable. The timeline, the descriptions, and the specific venom all point directly to Harlene Rosen and her sister. The song is a masterpiece of cruel specificity, laying bare a vulnerability and rage that Dylan would later learn to cloak in more poetic ambiguity. For Harlene Rosen, “Ballad in Plain D” was a devastating, very public airing of their private grievances, immortalizing her in the worst possible light for millions of listeners. It stands as the definitive, painful proof of her role as a muse—not of beauty, but of cathartic anger.

Dylan’s Regret and the Weight of Legacy

In later years, Bob Dylan expressed profound regret for “Ballad in Plain D.” In his 2004 memoir, Chronicles: Volume One, he called it an act of cruelty, stating he “looked at it as a mistake” and that writing it made him feel ashamed. This rare moment of contrition is telling. It acknowledges the real human on the other side of the art, the person whose life was framed by his pen for the sake of a song. Dylan’s regret does not erase the song’s existence or its impact on Harlene Rosen, but it does add a poignant postscript to their story.

This regret also reflects Dylan’s artistic evolution. He moved from the confessional, journal-entry style of his early years toward the rich, symbolic, and impersonal mythology of his mid-60s work and beyond. The lesson, perhaps learned too late for Harlene Rosen, was that the greatest art often comes not from transcribing personal history, but from transforming it into universal myth. His later muses—from Sara Lownds to the biblical and literary figures that populated his songs—were treated with more obscurity and, arguably, more protection.

The Person Beyond the Paragraph

The tragedy of the muse archetype is the erasure of the individual. So, who was Harlene Rosen outside of Bob Dylan’s story? After the breakup, she built a life. She earned a doctorate, became a respected psychologist in New York City, and authored professional papers. She married and had a family. By all accounts, she lived a full, accomplished, and private life, a stark contrast to the frozen, scorned figure in “Ballad in Plain D.” She rarely spoke to the press, offering only a few terse comments over the decades.

This deliberate silence is powerful. It represents a reclamation of self. Harlene Rosen was not a character waiting in the wings of history; she was the author of her own narrative. By choosing a path of professional contribution and personal privacy, she rejected the reductionist label of “Dylan’s ex-girlfriend.” Her life after Hibbing is a testament to the fact that the people who inspire art are complete, complex humans with their own stories, far richer than the fragments captured in a song, no matter how famous.

Cultural Context: The Woman Wronged in Folk and Rock

The story of Harlene Rosen sits within a long and often uncomfortable tradition in music where women are portrayed as antagonists in songs of heartbreak and spite. From blues classics to punk ragers, the “woman who done me wrong” is a staple trope. This dynamic raises persistent questions about ethics, gender, and ownership of narrative. The (typically) male artist holds the microphone and thus the power to define the relationship for the public, often without consent or right of reply.

Examining Harlene Rosen’s experience forces us to confront this power imbalance. While female artists certainly write scathing songs about men, the scale and cultural weight of the canonical male songwriter’s output have historically dominated. The muse, in these cases, has little recourse. Harlene Rosen’s response—a successful, silent life beyond the fame—becomes a form of dignified resistance. It is a reminder that the song is not the final truth; it is merely one perspective, immortalized in melody.

The Ultimate Guide to Garfield Hackett: Understanding the Pioneer and the Principles

The Lasting Impact on Dylan’s Artistic Trajectory

The emotional material of his relationship with Harlene Rosen provided Dylan with his first major foray into using personal anguish as direct lyrical fodder. The raw, unvarnished quality of “Ballad in Plain D,” while later regretted, was a crucial step in his development. It represented an extreme on the spectrum of confessional songwriting. By going too far, he may have learned where the line was for him, pushing him toward the more imaginative, allegorical style that would soon erupt in albums like Highway 61 Revisited.

Furthermore, the intensity of that early bond and its explosive end likely shaped his approach to future relationships and their portrayal in song. The protective obscurity he later employed suggests a learned caution. The ghost of Harlene Rosen, and the fallout from that song, may have haunted his creative process, teaching him that some things are better felt through a veil of symbolism than stated in plain, cruel D.

Comparative Analysis: Harlene Rosen and Other Dylan Muses

To fully appreciate the unique role of Harlene Rosen, it is instructive to compare her to other significant women in Dylan’s life and work. Each relationship provided different creative fuel and was processed through his evolving artistic lens.

| Muse Figure | Relationship Period | Key Songs/Influence | Nature of Portrayal | Artistic Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harlene Rosen | Late 1950s (Hibbing) | “Ballad in Plain D,” “Song to Woody” reference | Literal & Vitriolic: Direct, biographical, accusatory. The muse as antagonist in a personal drama. | Raw, confessional style; a lesson in the cost of lyrical literalness. |

| Suze Rotolo | Early 1960s (NYC) | “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right,” “Boots of Spanish Leather” | Poetic & Melancholic: Emotional but veiled in metaphor. The muse as inspiration for songs of love, loss, and independence. | Mastery of the bittersweet folk ballad; emotional depth with artistic distance. |

| Joan Baez | Mid-1960s | “Visions of Johanna,” various live duets | Mythic & Competitive: A peer and rival. The muse as a fellow titan, inspiring both admiration and a push to greater heights. | Fueled his move into electric rock; relationship dynamic reflected in complex, imagery-rich songs. |

| Sara Lownds | Mid-1960s to 1970s | Blonde on Blonde (aura), “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands,” “Sara” | Archetypal & Divine: Shrouded in symbol and worship. The muse as an almost religious figure, the center of a domestic idyll and later, its loss. | Peak of symbolic songwriting; creation of a profound personal mythology. |

| Carolyn Dennis | 1980s | “Emotionally Yours,” “Silvio” | Private & Acknowledged: A protected relationship with little direct lyrical fingerprint during its duration, later acknowledged. | Demonstrates a mature shift toward privacy, separating lived life from artistic output. |

This table illustrates Dylan’s journey from the painfully specific to the gloriously abstract. Harlene Rosen stands at the very beginning of this arc, the raw nerve before the poet learned to translate feeling into symbol.

The Ethical Dimension of Artistic License

The story of Harlene Rosen inherently poses difficult ethical questions. Where does artistic license end and the right to privacy begin? Does the transformation of a real person into art justify the potential harm caused? There is no easy answer. Society has traditionally sided with the artist, valuing the cultural output over the personal fallout for the individuals who inspired it. We celebrate the song without always considering its subject.

The case of Harlene Rosen is a prime example of this tension. Dylan’s artistic need to process and expel his feelings resulted in a work of great emotional power for listeners, but at a significant personal cost to her. It forces fans and critics alike to sit with this uncomfortable duality. Can we, and should we, separate the art from the real-life injury it may have caused? Engaging with this question is part of engaging with the full, human history of the art we love.

Reclaiming Narrative in the Digital Age

In today’s world, the dynamic between artist and muse is rapidly changing. Social media gives everyone a platform. A person immortalized unflatteringly in a song now has the potential to tell their side of the story publicly, to shape their own narrative in real-time. This represents a significant shift in the power structure that defined experiences like that of Harlene Rosen. While she chose dignified silence, modern “muses” might choose a tweet, an Instagram post, or even their own song in reply.

This democratization of narrative complicates the traditional muse mythology. It makes the artistic process more dialogic and less authoritarian. While it may not prevent artists from drawing from life, it introduces a potential for immediate public accountability that did not exist in the 1960s. The ghost of Harlene Rosen reminds us of a time when the microphone was held by only one party in a broken relationship, a paradigm that is no longer absolute.

The Enduring Fascination with Forgotten Figures

Why does the story of Harlene Rosen continue to captivate music historians and fans? It is precisely because she is a forgotten figure. She represents the buried foundation upon which a colossal career was built. There is a haunting quality to these early influencers who vanish from the official story. They are the human roots of the myth, and in uncovering them, we feel we are getting closer to the unvarnished truth of the artist’s genesis.

Furthermore, her story is a relatable human drama of first love, intellectual rivalry, and painful growth. It’s a narrative that exists far from the stadium stages and magazine covers, in the messy, real world where great art is often born. The fascination with Harlene Rosen is a fascination with origin itself—the spark, the fuel, and sometimes, the explosion that creates something new and world-changing.

The Quote That Captures the Dynamic

Reflecting on the complex interplay between life and art, music critic Greil Marcus once offered a insight that perfectly frames the Harlene Rosen narrative: “The best songs are never simply about what they seem to be about. They are about the singer, the subject, and the ghost of the truth that hangs between them.” This eloquently describes the territory Dylan navigated, especially in his early work. “Ballad in Plain D” was explicitly about what it seemed to be about, which may be why Dylan later rejected it. The “ghost of the truth” between him and Harlene Rosen was too starkly illuminated, leaving little to the imagination and, perhaps, violating the unspoken contract of artistic transformation.

Conclusion: More Than a Footnote

Harlene Rosen’s legacy is multifaceted. To music history, she is an essential, if painful, footnote in the biography of Bob Dylan—the first muse to be sacrificed on the altar of his songwriting. To the study of creativity, she is a case study in the catalytic power of real human relationships, especially those that end in fire. To the ethical discourse surrounding art, she is a reminder of the human cost that can accompany cultural treasure. And most importantly, to herself, she was Dr. Harlene Rosen, a woman who lived a full and consequential life far beyond the confines of a three-minute record.

Her story teaches us that behind every legend are real people with real feelings. The songs may last forever, but so too should our understanding of the complex, often difficult, human exchanges that made them possible. Harlene Rosen was not just a name in a liner note or a vicious verse; she was a person, a partner in a pivotal chapter, and a quiet reclaimant of her own story. In remembering her, we remember that art is born not from deities on Olympus, but from the flawed, passionate, and brilliantly human interactions that happen in places like Hibbing, Minnesota.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Who exactly was Harlene Rosen?

Harlene Rosen was a high school girlfriend of Bob Dylan (then Robert Zimmerman) in their hometown of Hibbing, Minnesota, in the late 1950s. She is widely recognized as the primary subject of his venomous 1964 song “Ballad in Plain D” and is considered one of his earliest and most impactful muses, influencing his transition from personal experience to lyrical art.

What is Harlene Rosen’s connection to the song “Ballad in Plain D”?

The song is an excruciatingly detailed, eight-minute account of a romantic breakup and a subsequent argument with the former lover’s sister. Biographical details and Dylan’s own later hints confirm that Harlene Rosen and her sister were the direct subjects of this deeply personal and vindictive track from the album Another Side of Bob Dylan.

How did Bob Dylan later view the song about Harlene Rosen?

Dylan expressed significant regret for writing “Ballad in Plain D.” In his memoir Chronicles, he called it a mistake that made him feel ashamed, acknowledging it as an act of cruelty. This regret marks a turning point in his artistic approach, moving him away from such literal, confessional songwriting toward more symbolic and universal themes.

What did Harlene Rosen do after her relationship with Dylan?

Harlene Rosen moved on to lead a very private and accomplished life. She earned a doctorate, became a practicing psychologist in New York City, authored professional works, and raised a family. She deliberately stayed out of the public eye, rarely commenting on her connection to Dylan, effectively reclaiming her narrative through a life of professional contribution and personal privacy.

Why is the story of Harlene Rosen still relevant today?

The story of Harlene Rosen remains relevant as a timeless case study in the ethics of art, the concept of the muse, and the human source of creative genius. It prompts discussions about the power imbalance in storytelling, the right to privacy, and the often-overlooked lives of the real people who inspire iconic works. Her experience is a foundational chapter in understanding Bob Dylan’s artistic evolution.